Updated April 2, 2018

If you are a connoisseur of media politics the 1960 presidential debates between John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Richard Milhous Nixon brought attention to the power of television and the declining importance of radio. The groupthink about the debates is that Kennedy won over the television debate audience while Nixon reigned over those who heard it on the radio. Was there such a disparate reaction to the candidates? Would Kennedy have lost to Nixon if the debates were not televised?

In looking at the Boston Globe’s coverage of the debates and the election, the supposed dichotomous television and radio public reactions to the Kennedy-Nixon debates and the assumptions surrounding its impact on Kennedy and Nixon are simply myths quoted as facts. Most importantly, the so-called facts supporting this myth are based on Kennedy and Nixon’s presidencies and not the debates themselves.

Unfortunately, it is a foregone conclusion to many historians, political operatives, political junkies and those in-between that Nixon lost the election because Kennedy beat him during the first televised debate on the image factor. Nixon looked tired. Kennedy was vibrant. Nixon seemed cranky. Kennedy was hopeful. Nixon was nervous and sweaty. Kennedy was confident and relaxed. Then in the same breath these same individuals proclaim that Nixon was the winner of the debate for those who tuned in via radio instead of television. Nixon is then described as strong versus Kennedy’s hesitancy. Nixon was knowledgeable. Kennedy was a neophyte. Nixon’s enunciation was clear. Kennedy’s accent made it hard to understand him.

A whole cottage industry on the media-effect of the Kennedy-Nixon debate has sprung up since the 1960 election. Most interesting, the analysis that Kennedy won the televised debate and Nixon the radio version is like an urban legend that has been infinitely repeated until it became accepted gospel.

1960 Political/Cultural Climate & The Boston Globe

The 1960 presidential election was of importance to the American electorate because of the changing political and cultural landscape. At that time Americans had international concerns about the spread of communism, exemplified by then Soviet Union President Nikita Khrushchev. The Russians were believed to be interested in the destruction of democracy and the United States, not necessarily in that order. Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro had confiscated over $770 million of U.S. property in response to the U.S. embargo of their country. The Berlin Wall was under construction in East Germany. France tested its first atomic bomb, as they became a nuclear power along with the United States, the United Kingdom and what was then known as the USSR.

Stateside the country was facing civil unrest over the enforcement of school integration as a result of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Also, then President Dwight Eisenhower signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which provided voting rights protection and prohibited voting obstruction. The iconic image of the civil rights movement for the year was of four African-American students who decided to stage a sit-in at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Other signals of cultural change were the U.S. Drug Administration’s approval of the first oral contraceptive and the publication of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, the best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about criminal injustice.

Many of the major city newspapers such as the Boston Globe covered the international events with as much intensity as they did local coverage. The Globe prided itself on its international coverage and had various foreign bureaus in Moscow, East Asia, the United Kingdom and Africa. Locally, the paper covered primarily the Greater Boston area, which included six counties and parts of Rhode Island and New Hampshire.[1]

The history of the Globe began in 1872 with a group of Boston businessmen and a $150,000 investment.[2] By 1960 the paper had more than 300,00 subscribers[3] that read its daily morning, afternoon, evening and Sunday editions.

The contents of the Boston Globe back then were about the same as the typical newspaper today. The paper had several sections such as the main/headline news, editorial, sports, style, entertainment and classifieds section. Interestingly, the style section had a subsection dedicated to its female readers titled “Women’s Section.” These articles were normally about cooking, the latest fashions, conducting the proper dinner party, how to raise proper children and what you need to do to keep your husband happy. The sports section was pretty expansive with heavy coverage and action photo shots on professional sports, mostly the Boston Red Sox and college football. Since it was the year of the Summer Olympics Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) received a lot of newspaper coverage for his gold medal in boxing. The editorial and main pages were mostly in synch topically, whether the subject was on the Cold War, poverty, education or local corruption. As for the classifieds section it was easily several pages in length with more than twenty advertisements per page.

As for its readership, the newspapers’ audience was primarily white; therefore its contents were directed towards that audience. Though 1960 was a year of pivotal civil rights issues, images or news about Blacks, beyond the sports section were generally absent from the Globe. The Boston Globe also looked much like the other large metropolitan papers in font-style and its use of photographs. The font was Times Roman and its photographs weren’t too fancy, with many of the subjects caught in close-up facial or full-length body shots.

The articles themselves varied in size from blurbs, to several paragraph to investigative-length pieces. What is interesting is that a good portion of the articles carried over to a second page, even if some of them could have fit on one page. The paper looked and felt as if it was cramming as much news as possible so that its readers would be truly informed, even though they were sometimes publishing three daily editions.

Overview of the Candidates

At the time of the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy was 43 years-old and in his second term as the junior Senator from Massachusetts, this after serving six years in the House of Representatives for Massachusetts’ 12th district. Nixon at 47 was in his second-term as the Vice-President of the United States under President Eisenhower. Prior to his vice-presidency, Nixon had been elected to the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate from the state of California.

Kennedy, who graduated from Harvard, was young, handsome, intelligent and rich who happened to be married to an elegant and beautiful wife. He was viewed as someone on the rise, primarily due to his family connections, as a man with new ideas, though his Senate voting record sometimes didn’t follow the party line. That is, when he actually was present to vote in the Senate. He had missed a lot of voting sessions due to ongoing back problems that were exacerbated by his World War II war wounds. Kennedy had gained national prominence by finishing second in the 1956 vice-presidential nominee balloting at the Democratic Convention. The following year he received a Pulitzer Prize for his book Profiles in Courage. Though by 1960 Kennedy had given the now-famous ‘New Frontier’ speech about new ideals and public service to “combat poverty, ignorance, [and] war,”[4] his nomination was still viewed as “more of a triumph of organization and evaluation than of deep dedication.”[5]

Nixon’s personal and political background was a bit less meteoric, but still noteworthy. He had worked at his family’s grocery store while pursuing his undergraduate degree at Whittier College. He finished second in his class at Duke University’s School of Law. Nixon was a practicing attorney when he signed up for the U.S. Navy after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He served in the Navy for four years where he rose to the rank of Lieutenant Commander during World War II. Nixon first gained national attention due to his House Un-American Activities Committee work that helped convict alleged Soviet Spy Alger Hiss. He was only 39 when he was selected by Eisenhower to be his vice-president. In 1952 Nixon gave his famous “Checkers” speech on national television in which he defended himself against influence-peddling allegations in order to remain on the ticket. As vice-president Nixon expanded the office’s role beyond Congressional legislation into national security matters. A prime example of this was his unplanned 1959 “Kitchen Debate’” with Khrushchev in which Nixon had “stood up to the bully.”[6] Along with his friendly wife and young daughters, Nixon had garnered a lot of prestige and goodwill with the Republican Party and the public by the time he ran for president in 1960.

Aside from the usual political party stances (conservative versus liberal) on policy issues the candidates agreed much more than they disagreed. For example, they both planned to combat poverty, support American farmers, strengthen the education system, build up the economy, and protect the civil rights of Negroes (the vernacular used at that time for Blacks/African-Americans). Even Nixon had agreed that the differences between him and Kennedy were not so much in their goals, but in the means of achieving them. By the time the first debate rolled around Roscoe Drummond of the Globe said that the debates would hopefully “enable [the public] to appraise the candidates face to face” so that we can look at their “divergent statements back to back.”[7]

Coverage of the Candidates

The Globe’s coverage of the candidates was mostly even-handed, surprising given the fact that Kennedy was a Boston politician. The paper apparently made a point of providing nearly daily coverage of each candidate’s campaign stops, policy statements, spousal comments with photos, and columnists‘ comments in support of Nixon or Kennedy. The stories on each candidate would appear on the same page, opposite pages or in the main news section. For example, in mid-September the Globe had an article titled “Jack Tells Nation He’d Outdo Reds” in which he criticized President Eisenhower’s handling of Soviet President Khrushchev and how he would deal with Russia and its president.[8] On the same page was another article, “Nixon Would Suspend Criticism of Defense: Asks Moratorium While Reds Swarming Here” in which Nixon states that Kennedy is playing into the communists’ hands by criticizing America’s strategy against the Russians.[9]

However, there were times that the Globe’s even-handed treatment of the candidates was absent. On occasion the paper referred to John F. Kennedy as ‘Jack’ not ‘Kennedy’ or ‘Senator Kennedy.’ Richard Nixon for the most part was referred to as ‘Nixon.’ Sometimes the use of Nixon’s name with his title ‘Vice President Nixon’ appeared in the body of the article. There were a couple of times during the pre/post debate coverage in which the paper used the candidates’ nicknames (‘Jack’ and ‘Dick’)[10] in the same article.

The pre-debate articles showed separate photos of the candidates, set-up to face each other with the text of the column in the middle. Yet, the caption under the pictures could paint a slightly different picture. Nixon’s photo caption describes him as a “master debater” with Kennedy’s caption stating that he’s a “also a good talker.”[11] It would appear that the columnist, John Harris, for this particular article might have a slight bias. Another nickname usage example was in the evening edition of the paper after the first debate, which was titled “Jack, Dick Survey Soviet Economic Surge at Close of Historic Debate.”[12]

Also, in an editorial by Ralph McGill, a day after the debate refers to Kennedy as “Senator Kennedy” while Vice President Nixon is called “Mr. Nixon.” Of note is in the first paragraph he calls the candidates “Messrs. Kennedy and Nixon.” However, for the most part the paper used the candidates’ last name without their official titles throughout the Globe’s campaign coverage. One can conclude that maybe some of the columnists showed their Kennedy preference, if not necessarily the newspaper as a whole. Regarding Nixon, neither the Globe nor its columnists seem to have favored or expressed disfavor with Nixon, as if they were abstaining from making an opinion.

The rest of the coverage of the candidates such as photos and inside personal stories were perfunctory at best. The candidates were usually photographed close-up, smiling, waving or shaking hands at various campaign stops. You could never tell where they were campaigning because the photos were focused so tightly on the candidates. Their facial expressions rarely changed from relaxed or serious, except when they were emphatic about something. Then you would see the candidate pointing their fingers or their lips pursed, caught in the middle of a statement. Maybe the photographs were so general in nature because they were via the Associated Press and not the Globe.

Of note is the fact that the Globe hardly spent anytime on the candidates’ religious backgrounds, especially Kennedy’s Catholicism. Nixon was a Protestant so his religion wasn’t viewed as a problem. However, Kennedy’s Catholicism was considered a big issue because of American anti-Catholic sentiments. Many wondered whether he would follow the dictates of the people or the pope. Kennedy eventually felt compelled to state that:

I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party candidate for president who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for the Church on public matters – and the Church does not speak for me.[13]

The day before the debate coverage the Globe printed an article by Samuel Lubbell, a syndicated columnist and public opinion analyst. Lubbell stated that if Kennedy would lose the presidential election “it will not be primarily because he is a Catholic.”[14] The article goes on to mention that Lubbell found “more persons shifting from their past voting habits because of religious considerations” but that a “widespread feeling” that Kennedy lacks experience in foreign affairs was hurting his candidacy.[15] Maybe another reason why the Catholicism issue was not addressed much in the paper was because its readers were mostly Catholic and therefore saw this angle as irrelevant.

Though some at the Globe may have favored Kennedy for president prior to the paper’s official endorsement of Kennedy, its coverage did not significantly reflect the newspaper’s preference. Maybe the paper was adhering to journalistic objectivity in that they wanted to be a source of information and not just an assumed Kennedy supporter. Also, the paper may not have seen Kennedy as a favorite son given his tenuous connection to the Boston area. Kennedy had only lived in the Boston area up to the age of ten before his family relocated to New York. Afterwards he attended boarding schools and college outside of Massachusetts. Though Kennedy was a Massachusetts Senator, the Globe may have been sensitive to the idea that other journalists or the public would think that they were automatic Kennedy supporters, hence their balanced coverage.

Pre-Debate Coverage of the 1st Debate

When Kennedy and Nixon agreed to participate in the nation’s first televised presidential debate it did not come with much fanfare, given its media significance. Besides it being the first televised debate it was also the first debate between presidential candidates since future presidential candidates Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas’ famous verbal duels in 1858 to represent Illinois in the U.S. Senate.

The Globe’s first article announcing the Kennedy-Nixon debate was published at the end of August 1960.[16] The article did not appear on the front page, and it was only seven short paragraphs in length. It mentioned that the first debate would last an hour; occur in Chicago on September 26th and the topic would be domestic affairs. Also, that there would be three other debates to occur sometime between late September through October. As for any potential hyperbole, the article added that the debate would be “history’s first face-to-face television and radio debates between major party nominees for President of the United States” and that Lincoln and Douglas could have never “dreamed of the vast audience” that Nixon and Kennedy will reach.[17] In addition, unnamed congressmen predicted that the candidates’ appearances “may revolutionize political campaigning by substituting the living room for the county fairgrounds or the rear platform of a cross country train.”[18]

After this semi build-up the Globe didn’t mention the upcoming first debate again until three days before the scheduled debate. In between the announcement of the debates and the actual debate the Globe published articles on the Kennedy and Nixon campaign travels, speeches, comments from their supporters and critics and political zingers that the candidates aimed at each other. The Boston voters did not see the historic significance to the upcoming debate either. In a Letter to the Editor dated September 25, 1960 a voter said that he could not “detect any difference” between Kennedy and Nixon and that they both “spout pious, vaporous platitudes, but some of their statements give you an idea of their make-up.”[19]

Nevertheless, Kennedy and Nixon continued to campaign on their strengths and differences. Kennedy’s continued with his platform that the Eisenhower Administration was out of new ideas and that the nation had ground to a halt. Nixon reiterated he had the requisite experience to help the United States get through the difficult times that were ahead.

Three days before the debate, the Globe placed news of the upcoming debate on the first page, albeit at the bottom of the page. The article said that there was an “air of tenseness in both camps” and that the televised and radio broadcast of the debates will “literally blank out all other programs.”[20] It added that Nixon, Kennedy and their staff were busy with “final preparations” and are “keenly aware of the high stakes.”[21] The editorial section had more of a promotional quality to its write-up of the debate. It commented that:

It would be appropriate and useful for those who expect to vote Republican to listen to Sen. Kennedy with special attentiveness and for those who expect they are going to vote Democratic to listen to Vice President Nixon with extra care.[22]

The day of the debate another editorial said that the televised argument would allow for “voter enlightenment” due to the “mingling of claims of the Republican candidate” and the “assertions” of the his Democratic foe.”[23] Another article reminded its readers about the debate’s start time, parameters, its topic and that it could have a “devastating potential to make or break their campaign for the presidency.”[24]

Post 1st Debate Coverage

The first debate was watched by over nearly 75 million[25] viewers, though it was a sedentary affair. The candidates sat in chairs with a table between them except when they had to approach the lectern to make their opening and closing statements and during the Q & A section. The domestic affairs questions were on the topics of American poverty, civil rights for minorities, better education, the economy and why each thought they would be the better president. There weren’t any verbal miscues or raised voices, except possibly on how the federal government was going to pay for these social programs. Overall it was a polite debate.

The day after the debate editorial comments from outside the Boston area such as The New York Times described the debate as “at times, interesting, but at no time [an] inspiring picture” of the candidates[26]. The Milwaukee Journal said that the debate was “unprecedented,” that it was “exciting” and most of all “informative.”[27] The Seattle Times hoped that in future debates Kennedy and Nixon would “trade their verbal punches with less restraint and with less of an eye on the stopwatch.” The New York News called out the broadcasting industry in their criticism, asking, “If the TV tycoons won’t let Kennedy and Nixon at least try to do as well as Lincoln and Douglas did, why go on with [these] powder puff performances?”[28] News icon Edward R. Murrow stated, “after last night’s debate the reputation of Messieurs Lincoln and Douglas is secure.”[29]

The candidates’ own thoughts on the debates were bland at best. Kennedy said that the debate was “very useful” and that this and subsequent debates “could prove to be very important.”[30] Nixon through his press secretary said he felt good about the debate.[31]

As for the Boston Globe, its next day coverage of the debate was objective, sticking with analyses and opinions based on text of the debate. The newspaper’s headlines asked “Who Won On TV? You Guess,” described the candidates as “Aggressive Kennedy, Intense Nixon Array Beliefs in Sharpest Focus,” claimed that “Debate Proves There Are Differences Between Candidates,” or stated that “Jack, Dick Survey Soviet Economic Surge at Close of Historic Debate.” The articles themselves provided debate highlights and more descriptive comments on how the candidates answered the questions or looked when the other was responding to a question such as Kennedy looking tense or when Nixon glanced down.[32]

Opinions on the debate came from academics, Globe columnists and Boston voters. Globe columnist Charles Claffey interviewed Bostonians at a “fashionable” hotel for their debate thoughts.[33] John Bartlett said that the debate “reaffirmed [his] conviction beyond a shadow of a doubt” that Nixon is his choice for president.[34] Lorie Walsh said that “she was a neutral” before watching the debate and that [she still is].”[35] Frank Mullin said Kennedy “better expressed the views of the American public than Vice President Nixon.”[36] Priscilla Howe, an independent voter thought, “both Kennedy and Nixon gave a wonderful show.”[37][38] One unnamed television viewer said that they didn’t like either candidate, that they were “both hams.” Another Globe columnist, Douglas Crocket also spent time at a bar interviewing male voters. The bar patrons said that they became “bored” with the debate and that Nixon “agreed too much” with Kennedy.[39] The Globe also took part in a newspaper pool with twelve other newspapers in which they all contacted a “Joe Smith” in their area to get their opinion of the debate. Boston’s Joe Smith said that “Kennedy appeared more sincere” and “Nixon appeared more hesitant and hedging.”[40] The other Joe Smiths located in other areas such as Seattle, Washington, DC, and Minneapolis also favored Kennedy.[41]

Globe columnists wrote up their opinions a couple of days after the debate. Sal Pett said that Nixon did better in the debate because of his “folksiness” in that he “engaged in good fellowship” and that his career “follows the traditional American success story.” Joseph Alsop said, “neither man fell flat on his face.”[42] John Crosby said, “Kennedy outpointed Nixon,” but that the candidates were “awfully cautious.”[43] Roscoe Drummond said both looked “scared and somber” and that Nixon was quick with a rebuttal and Kennedy showed a “full mastery of his subject matter.”[44]

In the Globe’s Letter to the Editor section several Boston voters had opinions about the debate all across the sphere, that “Kennedy has the best answers to the ills of our country;” others said that “neither gave any indication” that they differed from their respective party’s predecessors, and that while another believed that “neither [is] a genius, but they like Nixon.”[45]

Besides the candidates’ handling of the debate, a few articles had popped up about how they looked during their televised appearance, with the articles concentrated on Nixon. After the debate there were comments about Nixon’s health and appearance, that he looked like he had lost weight that he was worn out. The image issue was first mentioned in an article the day after the debate, in which Nixon said “[he thought he] lost a couple of pounds and it [might have shown] up on his face.”[46] Right next to this column was another article about Nixon’s appearance. Nixon’s wife is quoted as saying her husband “looked wonderful on [her] TV set” in response to a reporter’s question if she thought her husband looked tired and thinner.[47]

Two days later Nixon’s debate appearance started receiving more coverage. Columnist Doris Fleeson wondered if Nixon’s diet and bad knee hurt his television appearance. She mentioned that Nixon dieted to lose his “pudgy look” and to “tame his jowls” and that his infected knee as a result of surgery created “an awkwardness in his stance.”[48] As for Kennedy, she said that the “cruel cameras were kind to his rounded face” which “refuses to betray campaign fatigue.”[49] Fleeson’s colleague, Ralph McGill said that Kennedy “seemed fresher” and that Nixon “didn’t look too good.”

Later articles in the Globe inquired about Nixon’s health. A physician traveling with Nixon said that there was nothing wrong with the vice president. This same article was also the first time that Nixon’s debate makeup was mentioned as being a problem. Herbert Klein, Nixon’s press secretary attributed Nixon’s haggard look to the TV lights or the makeup he wore.[50]

Don Hewitt, producer of the first debate recalled asking the candidates in the presence of each other if either of them wanted makeup. Both candidates declined, but Hewitt said that he noticed Nixon really needed makeup to “cover a sallow complexion and a growth of beard . . . I think.”[51] Hewitt added that Nixon’s advisors did a “dumb thing” by not using the professional make-up artist who had come to do the candidates. Instead Nixon’s advisors “smeared him with a slapdash layer of something called ‘shavestick’ that looked . . . terrible.”[52] Hewitt added that Kennedy was “well-tanned” from his “open-air” campaign stops in California.[53]

Nixon’s makeup problem turned into mini-drama for a few days. The Globe ran an article (originally published by the Chicago Daily News) stating that the Makeup Artists and Hair Stylists Union believe that his makeup artist may have sabotaged Nixon.[54] An agent for the union said that the makeup artist “loused [Nixon] up so badly that a Republican couldn’t have done that job.” The Nixon camp immediately stamped out this story while acknowledging that Nixon did not look good on television.[55] Even Eisenhower chimed in about the “trials of television makeup” and that it’s too bad that “Dick has such a heavy beard.” Luckily, Nixon’s appearance improved by the time of his televised Republican fundraising event, which occurred a few days after the debate. It was noted that his face had a “strong appearance” and his “emaciated appearance was not in evidence.”

Afterward, Nixon’s makeup and health issue stories disappeared as the Globe fell back to its usual coverage of the candidates’ campaigns, perceived problem voters and Khrushchev. Globe coverage of the second, third, and fourth debates was far less than the first, in contrast to the steady television viewership numbers. Nielsen ratings showed that 28.1 million homes (total persons/viewership not available) tuned into the first debate; 27.9 million for the second; 28.8 million for the third and 27.3 million watched the last debate.[56]

Kennedy was considered the winner of the first debate. Nixon was deemed the winner of the second debate, which was described as a “real slugfest.”[57] The third debate ended in a draw[58] with the 4th debate going to Kennedy.

Election Results

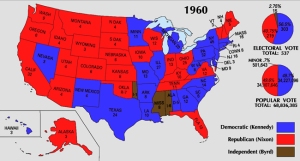

The 1960 presidential election was very close in that Nixon could have possibly won the election. The day before the election the Globe said that the final Gallup Poll’s nationwide survey gave Kennedy a very slight edge.[59] Kennedy only defeated Nixon by approximately 120,000 out of 68.8 million ballots cast.[60] Political Journalist Theodore White wrote that:

. . . the margin of popular vote is so thin as to be, in all reality, nonexistent. If only 4,500 voters in Illinois and 28,000 voters in Texas changed their minds, the sum of their 32,000 votes would have moved both these states, with their combined 51 electoral votes into the Nixon column.[61]

On November 8th, election day, the Globe’s evening edition projected Kennedy as the newly-elected president with big headlines and articles stating that a “record-size” election “piled up a margin” for Kennedy of “nearly 500,00 votes” over Nixon and that a “new generation has its chance.”[62] Another election article referenced Kennedy as “its favorite son” which was the first time that the Globe used such a description in its campaign coverage.[63] Nixon’s first debate appearance was mentioned in a Globe post-election editorial. Columnist Roscoe Drummond said that Nixon’s “5 o’clock” shadow” had “no place in [the] campaign” and that the debates caused the candidates not to deliver any “serious” or “substantial” speeches.[64]

Two days after the election more Globe columnists had article headlines such as “Liberals Had Their Day;” “The Country Wanted Him” and “Kennedy Calmly Accepts Presidency, Asks Nation to Help.” By the time the third day of post-election rolled around the Globe’s coverage concentrated on Kennedy’s naming of some of his Administration’s staff, a sign that the election was over as far many were concerned. Yet, in the middle of these administrative write-ups was an article about Nixon “not quitting yet” and finding “faint hope in [a] recount.”[65]

As for the comments from the Boston public about the election, it wasn’t the main topic of conversation based on Globe coverage. The newspaper did very little post-election interviewing or news articles of local voters as they did during the campaign. The Letters to the Editor section during the first three days after the election were on such non-election issues such as passengers being punished at Logan Airport, how to get a good job if you are over 50, and that the Boston area had a littering problem. The election was also old news as far as Bostonians were concerned.

However, there was an interesting September 11th article about Robert Kennedy, Jack’s brother stating that Kennedy would not have won the election had it not been for the televised debates.[66] The article also added that Robert Kennedy believed that the election would have been “difficult” if the debates had been “on radio alone.”[67] The article does not directly quote anyone from either campaign about these observations nor were there any post-election follow-up articles in the Globe about this radio-television analysis. Maybe the articles’ placement at the bottom of the page, along with the paper’s main headline being “Car Insurance Rates Up 11%,” signified the Globe’s lack of interest or belief in these conclusions.

Debate: Radio Audience vs. Television Audience

The myth that Kennedy won the television audience and Nixon the radio audience has been repeated so much that most consider it to be true or at least common knowledge. Anecdotes such as former Senator Bob Dole illustrate this myth. Dole recalled that he was “listening to [to the first debate] on the radio coming into Lincoln, Nebraska and thought Nixon was doing a great job.”[68] However, when he saw the TV clips the next morning he thought Nixon “didn’t look well” and that Kennedy looked “young and articulate, and . . . wiped [Nixon] out.”[69] The myth survives even though there are two important factors that undermines the myth’s truthfulness: 1) the number of debates and 2) audience statistics. First, the myth of Kennedy making TV mincemeat of Nixon because Kennedy was calm, cool and collected versus Nixon’s five o’clock shadow and sweatiness. Yes, Nixon did not look well in the first debate, but his appearance in subsequent debates had noticeably improved, and the story died. As stated earlier, Nixon lost the first debate, was declared the winner in the second debate, the third debate was a draw and the fourth debate slightly won by Kennedy. It is hard to conclude that Kennedy won the television debate crowd given the results of the additional debates.

Second, official data regarding the radio audience for the first debate or the other debates doesn’t exist. Though by 1960 over 52 million households[70] owned a television set, a substantial number of the population still relied on their radio for news and information. The debates were broadcast live via television and radio; only TV viewership was officially tracked for the debates.

Much of the debate radio statistics that are mentioned appear to be anecdotal and do not cite from an official ratings source. Articles state that at least 20 million[71] heard the debate or maybe it was 61 million.[72] Ralph MacGill of the Globe said that he had a number of persons listen to the great debate on the radio and they “unanimously thought that Mr. Nixon had the better of it.”[73] Except for MacGill’s anecdotal survey, the Globe did not make any statistical reference to radio listeners, just the total number of television viewers.

According to Pollster.com the only “true survey”[74] that attempted to gauge the debate reactions among television and radio listeners was conducted on November 7, 1960 the day of the elections. Sidlinger and Company did a telephone sample survey in which 282 persons responded.[75] Their survey said that 48.7% of the radio audience thought that Nixon won and 21% picked Kennedy; of the surveyed television audience 30.2% named Kennedy the debate winner with 28.6% picking Nixon.[76] Also, they projected that 270 million watched the debates and 61.4 million listened to them on the radio.[77]

Though this is the only known survey to track the radio and television audience, note that it did not survey either audience during or immediately after the first debate. Also the small sample size also makes the survey suspect. The fact that the survey is rarely mentioned, if ever, in support of the Kennedy-Nixon debate myth raises more flags than provide validation of the myth. As a result, the myth is never backed up with statistical evidence, just personal narratives and anecdotes, which have yet to be proven.

Conclusion

Based on the Boston Globe’s debate and election coverage it is safe to say that neither the first Kennedy-Nixon debate nor the latter debates had much of an impact on the electorate. More importantly, the media myth surrounding the television vs. radio reaction to the Kennedy-Nixon debates is not supported by the Globe’s coverage. The Globe did not concentrate on the candidates’ televised debate looks to Kennedy’s benefit and Nixon’s detriment nor did they publish any data supporting such viewer preference. Also, the Globe did not report any comprehensive radio listener survey or findings that supported radio listeners’ preference for Nixon over Kennedy.

As stated earlier, Kennedy and Nixon debated four times within a one-month period. If Kennedy’s debate performance was so strong and he looked so much better than Nixon, then why did he win by only 120,000 votes? The myth doesn’t have an answer for this particular fact.

Television did play an important part in the debates due to its novelty, not because of any Kennedy-Nixon imagery that significantly favored Kennedy. The Globe’s coverage talked about how interesting it would be to see presidential candidates on the same stage debating each other face-to-face, not on how they would look. The Globe was more fascinated by the millions of viewers who would simultaneously watch the first debate. Nevertheless, the Globe’s coverage emphasized the issues and how each candidate responded to the debate questions, not how they looked on television. The minimal amount of coverage about Kennedy and Nixon’s looks post-debates, especially Nixon’s, contradicts the myth that Kennedy’s handsomeness and Nixon’s paleness led to Kennedy winning the television debate audiences.

The myth that Nixon won the radio audience is also suspect based on Globe coverage. The Globe’s headlines talked about the millions of viewers who watched the first debate. Official and comprehensive radio viewership was not tracked by any polling service; nor mentioned in the Globe. The Globe only published anecdotal comments about how some local radio listeners thought Nixon won the debate.

Where the myth began to take shape and take on a life of its own is hard to determine. However, the myth’s believability is tied to Kennedy’s death and Richard Nixon’s pre/post-presidency years.

After losing the 1960 presidential election, Nixon went back to California after which he ran for governor of California in 1962, a race he lost. In 1963 Kennedy was assassinated, becoming historically frozen in time yet making gains in becoming one of the nation’s most admired presidents. Nixon ran again for president in 1968, finally winning after beating Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey and Independent candidate George Wallace on a platform promising societal stability.

By the time that Nixon was into his second term (1972-1976) his accomplishments were many. Unfortunately Nixon’s Watergate actions led to his 1974 resignation before he would have been impeached. Afterwards Nixon’s image was forever changed. Gone was the poor boy who obtained full scholarships to go to college and law school, who faced down Khrushchev, who went on TV for the first time and successfully fought for his honor; who battled his way back from potential political obscurity after the 1960 election, and who, as president signed the first arms control treaty with the Soviet Union. All that was left was a president who authorized and then attempted to cover-up the break-in of Democratic Party’s headquarters and who enjoyed taping conversations without anyone’s knowledge.

Nixon came to personify the worst of presidents while Kennedy came to symbolize the best. Nixon was ‘Tricky Dick’ while Kennedy was ‘Camelot.’ After Watergate other presidential candidates intentionally or unintentionally attempted to become the next Kennedy while Nixon was an emulation to avoid at all costs.

The avoidance of Nixon’s presidential missteps somehow morphed into a ‘how-not-to-do-a-debate” training video for politicians on the rise. Post-Reagan politicians saw Nixon as someone who didn’t know how to work the television media like Kennedy. This thought completely ignores Nixon’s successful media experience with his ‘Checkers’ speech where he defended his political integrity, his impromptu “Kitchen Debate’ with Khrushchev and his latter strong debates with Kennedy.

Yet, Nixon has become not only a bad president but also a horrible debater whose dark and sweaty visage was a precursor to his Watergate years. Kennedy had become the bright political light that politicians want to be and the public wants to lead their country.

As political pundits, consultants, and analysts have become and probably will continue to be part of political campaigns the Kennedy-Nixon debate media myth will be promulgated again and again. That is until some other candidates’ political actions knock Nixon and Kennedy off of their mythical media thrones. Then again, maybe this myth is here to stay, which is probably the only factual thing about it.

Note: American University journalism graduate paper submitted by Angelia Levy – March 2010

[1] “Company History,” Boston Globeonline (http://bostonglobe.com/aboutus/aspx), 28 February 2010 (accessed 1 March 2010).

[2] “Company History,” Boston Globe online (http://bostonglobe.com/aboutus/aspx).

[3] “Company History,” Boston Globe online (http://bostonglobe.com/aboutus/aspx).

[4] Thomas C. Reeves, Question of Character (New York, NY: The Free Press, 1991), 183.

[5] Reeves, Question of Character, 185.

[6] William Safire, “The Cold War’s Hot Kitchen,” New York Times online (http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/24/opinion/24safire.html) 23 July 2009 (accessed 20 February 2010).

[7] Roscoe Drummond “Studio Brinkmanship: Everyone Ought to Watch Monday’s Kennedy-Nixon Debate,” Boston Globe (24 September 1960): 23

[8] Robert Healey “Jack Tells Nation He’d Outdo Reds: Pledges 3-Point Program in 1st Major TV Address,” Boston Globe (21 September 1960): 1

[9] Robert Hanson “Nixon Would Suspend Criticism of Defense: Asks Moratorium While Reds Swarming Here,” Boston Globe (21 September 1960): 1

[10] John Harris “Jack, Dick Tense as They Clear Decks For Historic TV Encounter Tomorrow,” Boston Globe (25 September 1960): 29

[11] Harris,”Dick Tense as They Clear Decks For Historic TV Encounter Tomorrow,” Boston Globe.

[12] “Jack, Dick Survey Soviet Economic Surge at Close of Historic Debate,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 38.

[13] Kennedy, John F. (2002-06-18) “Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association” American Rhetoric. (http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jfkhoustonministers.html), 15 October 2007 (accessed 25 February 2010).

[14] Samuel Lubbell, “Issue of Religion Not Strong Enough To Swing Election,” Boston Globe, (26 September 1960): 28.

[15] Lubbell, “Issue of Religion” Boston Globe.

[16] “1st Jack, Dick TV Debate Sept. 26” Boston Globe (1 September 1960): 25.

[17] “1st Jack, Dick TV Debate Sept. 26,” Boston Globe.

[18] “1st Jack, Dick TV Debate Sept. 26,” Boston Globe.

[19] J.J. Riley “Neither Candidate To His Liking” Letter to the Editor, Boston Globe (22 September 1960): 26.

[20] “Kennedy, Nixon Bone-Up for Their Opening TV Battle on Monday,” Boston Globe (25 September 1960): 63.

[21] “Kennedy, Nixon Bone Up” Boston Globe.

[22] Drummond, “Studio Brinkmanship” Boston Globe.

[23] Uncle Dudley “Something Old, Something New,” Boston Globe (26 September 1960) 8.

[24] Rowland Evans, Jr. “Chicago Sets the Stage For Clash of Party Titans,” Boston Globe (26 September 1960): 6.

[25] “Great Debate Rightly Named: Nixon, Kennedy set a precedent that will be hard to abandon” Television Museum online (http://www.museum.tv/debateweb/html/history/1960/rightlnamed.htm), (accessed 18 February 2010).

[26] “Great Debate Rightly Named “ Television Museum online (http://www.museum.tv/debateweb/html/history/1960/rightlnamed.htm).

[27] “Great Debate Rightly Named “ Television Museum online (http://www.museum.tv/debateweb/html/history/1960/rightlnamed.htm).

[28] Kevin T. Jones, The Role of Televised Debates in the U.S. Presidential Election Process (Atlanta: University Press of the South, 2005), 10.

[29] “Debate Headlines” (http://www.museum.tv/debateweb/html/history/1960/headlines.html) (accessed 26 February 2010).

[30] “Debate Called Very Useful By Kennedy,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 8.

[31] “Nixon Health Given O.K.,” Boston Globe (29 September 1960): 21.

[32] “Who Won on TV? You Guess,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 1.

[33] Charles E. Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change Many Boston Votes,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 38.

[34] Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change,” Boston Globe.

[35] Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change,” Boston Globe.

[36] Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change,” Boston Globe.

[37] Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change,” Boston Globe.

[38] Claffey, “Debate Didn’t Change,” Boston Globe.

[39] Douglas Crocket,” Boys At Bar Get Bored; Nixon Too Agreeable,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 38.

[40] “Joe Smith, American, Does Not Change His Mind,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 25.

[41] “Joe Smith, American, Does Not Change His Mind,” Boston Globe.

[42] Joseph Alsop, “Personalities Show, Viewpoints Blur,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 19.

[43] John Crosby, “Nixon Better in Prepared Talk, Kennedy Won With His Rebuttal,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 22.

[44] Roscoe Drummond, “Kennedy Relied on Prepared Talk, Nixon More Original in His Rebuttal,” Boston Globe (28 September 1960): 19

[45] “What People Talk About: The Kennedy-Nixon Debate, An Appraisal,” Boston Globe (29 September 1960): 42.

[46] “Nixon Says Lost Weight Shows in Face,” Boston Globe (27 September 1960): 9.

[47] “Pat Sees Nixon 1st Time on TV ‘Looked Great,’” Boston Globe (27 September 1969): 9.

[48] Doris Fleeson, “Diet, Bad Knee Hurt TV Appearance,” Boston Globe (28 September 1960). 19.

[49] Fleeson, “Diet, Bad Knee,” Boston Globe.

[50] “Nixon Health Given O.K.,” Boston Globe.

[51] Gary A. Donaldson, The First Modern Campaign: Kennedy, Nixon and the Election of 1960 (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), 113.

[52] Donaldson, The First Modern, 115

[53] Donaldson, The First Modern, 115

[54] Richard Stout, “Nixon Sabotaged, Makeup Union Says,” Boston Globe (29 September 1960): 9, 16.

[55] “No Sabotage in TV Make-Up Says Nixon Aide,” Boston Globe (30 September 1960): 2.

[56] “Nielsen Television Ratings for Each of the Presidential Debates from 1960 through 2000,” Television Museum online (http://museum.tv.debateweb/html/equalizer/prints/stats_tvratings.htm), 2007, (accessed 20 February 2010).

[57] John Harris,” Real Slugfest This Time, Nixon Jack Toe to Toe”, Boston Globe (8 October 1960): 1.

[58] “John Harris, 3rd TV Debate Ends in Huff on Charge Kennedy Used Notes,” Boston Globe (14 October 1960): 1.

[59] George Gallup, “One Percent Edge Given to Kennedy,” Boston Globe (7 November 1960): 1, 10.

[60] Donaldson, The First Modern, 56.

[61] Theodore White, The Making of the President 1960, (Washington, D.C.: Harper Perennial, Reissue 2009).

[62] Lawrence L. Winship, “John Fitzgerald Kennedy Elected President,” Boston Globe (9 November 1960): 1, 17.

[63] John Harris, “Bay State Splits for Jack, Salty, Volpe, McCormack,” Boston Globe (9 November 1960): 1.

[64] Roscoe Drummond, “Empty Campaign But Fair, Clean,” Boston Globe (9 November 1960): 38.

[65] “Nixon Camp Not Quitting Yet, Finds Faint Hope in Recount,” Boston Globe (10 November 1960): 1.

[66] Charles Claffey, “Jack Couldn’t Have Won Without TV Debates,” Boston Globe (10 November 1960): 1

[67] Claffey, “Jack Couldn’t Have Won,” Boston Globe.

[68] Greg Botelho,“JFK, Nixon Usher in Marriage of TV, Politics” CNN online (http://www.cnn.com/2004/US/09/24/jfk.nixon.debate/index.html) 12 March 2007 (accessed 1 March 2010).

[69] Boetelha, “JFK, Nixon Usher in Marriage of TV, Politics” CNN online (http://www.cnn.com/2004/US/09/24/jfk.nixon.debate/index.html).

[70] Winthrop Jordan, The Americans (Chicago: McDougal Littell, 1996), 798.

[71] Robert Sanders, “The Great Debates,” Television Museum online (http://museum.tv/debateweb/html/greatdebate/print/r_sanders.htm. (accessed 26 February 2010).

[72] “Mark Blumenthal, “Did Nixon Win With Radio Listeners?,” Pollster online (http://www.pollster.com/blogs/did_nixon_win_with_radio_liste.php) (accessed 26 February 2010).

[73] David L. Vancil and Sue D. Pendell, ”The Myth of Viewer-Listener Disagreement in the First Kennedy-Nixon Debate.” Central States Speech Journal (Spring 1987): 18.

[74] Blumenthal,” Did Nixon Win With Radio Listeners?” Pollster online (http://www.pollster.com/blogs/did_nixon_win_with_radio_liste.php) (accessed 26 February 2010).

[75] Blumenthal,” Did Nixon Win With Radio Listeners?” Pollster online (http://www.pollster.com/blogs/did_nixon_win_with_radio_liste.php).

[76] Blumenthal,” Did Nixon Win With Radio Listeners?” Pollster online (http://www.pollster.com/blogs/did_nixon_win_with_radio_liste.php).

[77] Blumenthal, “Did Nixon Win With Radio Listeners?” Pollster online (http://www.pollster.com/blogs/did_nixon_win_with_radio_liste.php).

Perfect just what I was looking for! .

LikeLike

I enjoy, lead to I discovered just what I was taking a look for.

You’ve ended my four day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man.

Have a nice day. Bye

LikeLike

You’re welcome 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Sterling's Court.

LikeLike

Thanks for the blog shout-out!

LikeLike

Fantastic goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you’re just too excellent.

I really like what you’ve acquired here, really like

what you are stating and the way in which you say it.

You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it sensible.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is really a

terrific site.

LikeLike

Your high compliments re my post and site are much appreciated. I’m trying to get back to blogging regularly (at least once a week) – so people will have more to read 🙂

LikeLike

This is the right blog for everyone who would like to understand this topic.

You realize a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I personally

will need to…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic

that has been written about for a long time. Great stuff,

just great!

LikeLike

Thank you very much! My paper (which turned into a blog) was meant to provide info to those who’ve come fresh to this myth and others who are well-versed in it, with both sides coming away with more information or at least food for thought.

LikeLike

Incredible points. Keep up the great work.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kudos – much appreciated!

LikeLike

I’m curious to find out what blog system you’re utilizing?

I’m having some minor security issues with my latest website

and I’d like to find something more safe. Do you have any suggestions?

LikeLike

WordPress is my blog system. Been with them since Fall 2009. I’ve had zero problems with them (knock on wood). A lot of media news sites in the past year have joined the WordPress bandwagon. Whether you’re an HTML/coding guru or a tech neophyte WordPress will work for you.

LikeLike

My guess is that the shock of the assassination of Kennedy made a rather undeserving but not horrible politician into a hero. And that Nixon’s accomplishments and Kennedy’s lack thereof made Nixon a figure either feared or respected (Kennedy being neither, at least not until he had been dead for some time).

There was nothing particularly outrageous about Watergate, not in a government where burglary espionage bribery and murder were routinely used as policy tools, particularly abroad. What sank Nixon was to defy both the people and the entire political establishment at the same time. Let someone get away with THAT, and what you have is another Hitler, Stalin, and Mao.

LikeLike

I agree with you in re to Watergate not being “particularly outrageous” especially compared to some of the political and illegal shenanigans that city mayors have been up to since then let alone national politicos. A lot of political and cultural upheaval was going on post-JFK and during the Nixon years. Some Americans found it hard to stay balanced; they were expecting the federal government to hold things together for the country. Therefore to see their president (Nixon) acting like a burglar/spy, instead of as a representative of ‘American values and decency’ brought about anger, disappointment and heartbreak. Democratic U.S. presidents have suffered in comparison to JFK, but none have suffered as much as the republican Nixon.

LikeLike

I really love your blog.. Great colors & theme. Did you build this amazing site yourself?

Please reply back as I’m trying to create my own site and

would like to know where you got this from or exactly what the theme is called.

Many thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks for the blog compliment 🙂 I’m using the WordPress theme ‘Retrofitted’for my blog. I could’ve built the blog myself, but I would’ve never found the time to do it. Luckily WordPress.com makes it easier for people to format their blogs to their hearts content.

LikeLike

Thanks for citing me and providing a link to my blog. It’s much appreciated! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for the auspicious writeup. It in truth was a amusement account it.

Look complex to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how

can we keep up a correspondence?

LikeLike

Thanks for the blog compliments. I really enjoyed writing this paper (which became a blog) since it combined my love of research and election politics. As for reaching out to me, you can always contact me via my blog or Twitter 🙂

LikeLike

“Sidlinger and Company did a telephone sample survey in which 282 persons responded.[75] Their survey said that 48.7% of the radio audience thought that Nixon won and 21% picked Kennedy; of the surveyed television audience 30.2% named Kennedy the debate winner with 28.6% picking Nixon.[76] Also, they projected that 270 million watched the debates and 61.4 million listened to them on the radio.[77]

Though this is the only known survey to track the radio and television audience, note that it did not survey either audience during or immediately after the first debate. Also the small sample size also makes the survey suspect. The fact that the survey is rarely mentioned, if ever, in support of the Kennedy-Nixon debate myth raises more flags than provide validation of the myth. As a result, the myth is never backed up with statistical evidence, just personal narratives and anecdotes, which have yet to be proven.”

The sample size is adequate to conclude that the large difference in candidate preference indicates a real difference in preference, higher Nixon acceptance among radio listeners. But that doesn’t mean that the visual medium changed the viewer’s perception of the candidates.

The simplest explanation of candidate preference by television viewership has to do with the different demographics of television owners, by age group, region of the country, etc. That is, radio listeners were likely older, less affluent and more rural than television viewers, and so more likely to lean toward the more experienced Republican Vice President.

Like the sociological parable of the Eskimos’, better make that the Inuits’, supposedly larger vocabulary of snow words, some stories are so good that we can’t let the facts get in the way.

LikeLike

You do have a point re the radio demographics being a determinant as to why those listeners chose Nixon over Kennedy. What’s so funny about the myth is that the few that even mention the so-called “radio preference” don’t discuss the limited amount of info re the radio survey/sample size. The radio survey is discussed as if it was Gallup-size in nature (which it obviously wasn’t) and hundreds-to-thousands of people were surveyed for each debate. I’m not negating the possibility of a large majority of radio listeners-beyond the Sidlinger survey–selected Nixon as the debate winner. It’s that those who tell the myth need to do their homework, but even if they had the facts they would still tell the myth as is because it’s a politically good one.

LikeLike